Alternatively titled:

This changes everything! (How banks create money out of nothing)

AI Image courtesy of Bing Image Creator

Contents

Establishing that the money supply must grow

…why don’t they bail themselves out of financial trouble?

Introduction

In the articles written so far, this author has endeavoured to carry out an analysis of our nation’s factors of production. Land is covered here, and labour is covered in this and subsequent articles. It would be natural to cover capital next. Money, by some definitions, is but a sub-set of capital, but it is a critical sub-set, and so it is covered in this piece.

Money and its importance

Money, in short, is a medium of exchange. In today’s world, it refers to a nation’s currency, and broader definitions of a nation’s money can also include the currencies of other nations, as we shall see shortly.

It is true that money is important because without it exchange would be cumbersome and slow. However, what makes money even more important is that to misunderstand money’s role in the economy sets policymakers up to mismanage that economy. Misunderstood money is responsible for much of global economic mismanagement and dysfunction. For this reason, in this article we shall endeavour to start at the foundation / bedrock of an understanding of money, and to build upon that an understanding of how a nation’s money can be managed in such a way as to greatly augment that nation’s efforts at growth and job-creation.

Forms of money

In order to understand money, it is worth looking at the types of money. The fancy term used by economists to classify the various types of money is “monetary aggregates.” It is this author’s belief that the convoluted definitions of economics often play an obfuscatory role. Nevertheless we shall wax only slightly technical here, intending, as we do, to simplify these definitions. This brief section is as technical as we will get. The rest of the article will be simple to understand, and the monetary aggregates are introduced here only to provide a basis for understanding how the money supply changes with time.

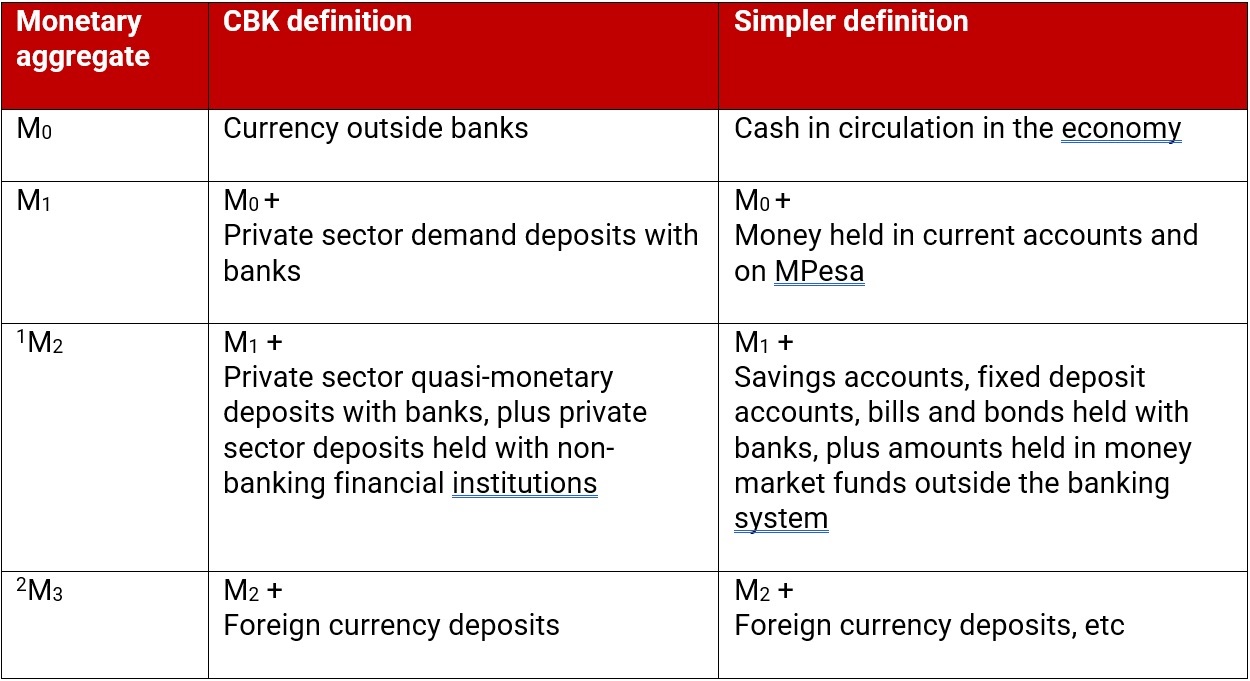

Below we list, according to the Central Bank of Kenya (the CBK), the various monetary aggregates.

Table 1: The Monetary Aggregates and their definitions

(Source: Central Bank of Kenya “Sources of Monetary Data”)

These are the various forms of money. The key monetary aggregates, as we shall see, are M1 and M2. (This is particularly true in our increasingly cash-less society.) We shall use these monetary aggregates to help us understand (a) that the money supply must grow, and (b) how exactly it does grow.

Establishing that the money supply must grow

At independence, Kenya’s population was 9 million, and our gross domestic product (GDP) was said to be USD 926.5M. At present, our population is 54 million, and our GDP is said to be USD 113.4B. It would be impossible to run the country on the same supply of money as that which existed at independence; currency shortages would persist. The money supply must necessarily keep pace with the growth of the economy. More finely, it must actually match it, for to exceed it results in one form of inflation or another.

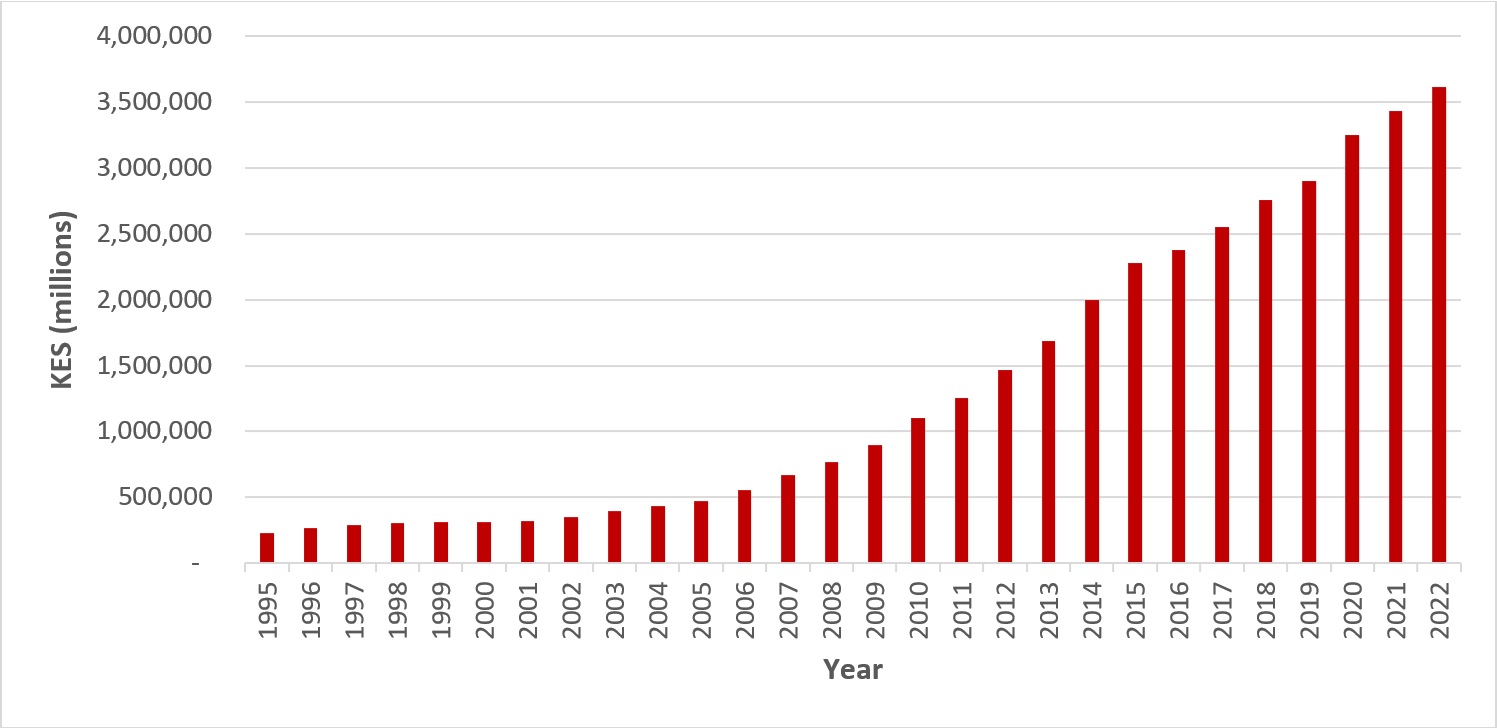

This portended growth in the money supply is borne out in the data. The graph below shows the growth of the Kenyan money supply from 1995 to 2022. It can be seen that our country’s money supply (taking M2 as the money supply aggregate) grew from KES 231B in December 1995 to KES 3.6 trillion in 2022.

Figure 1: Growth in Kenya’s Money Supply (M2) from 1995 – 2022

(Source: Central Bank of Kenya: Depository Corporation Survey)

How the money supply grows

A nation with its own currency creates its own money supply. To understand how the money supply grows, we must first dispense with a popular misconception: that the government (specifically, the CBK) creates our money supply. This is true, but to such a small extent as to be almost insignificant.

That portion of the money supply that the government creates directly is actually M0, which is cash. The government prints notes and mints coins, but notes and coins actually constitute a very small part of the total money supply. In December 2022, M0 (hard cash) was KES 258.8B, against a total money supply (M2)[3], (i.e. hard cash, money in current accounts and on MPesa, money in savings accounts, fixed deposits, bills and bonds held with banks, plus money in money market funds) of KES 3.6 trillion. In other words, notes and coins comprised a scant 7% of our money supply. Exclusive M1 components comprise 47% of our money supply, while exclusive M2 components comprise the additional 46% of our money supply.

In addition, while M0 (cash) has grown 8x since 1995, M1 has grown 37x, and M2 has grown 9x. Further, it is also true that savings deposits, fixed deposits, and money in non-banking financial institutions (money market funds and the like) were once bank deposits in one form or another. It is therefore clear that if we want to understand how the money supply grows, it is the growth of bank deposits – the growth of M1 – that we must examine.

So how does M1 (the key aggregate, since some of it eventually becomes M2) actually grow? The government does not deposit amounts in banks’ accounts which banks then lend. Neither (and here we must dispense with another misconception) is it true that banks lend deposits banked with them by depositors. This is a fallacy and obfuscation for which economic orthodoxy must take the lion’s share of the blame. The view of banks as “financial intermediaries,” harmlessly bridging the gap between savers and borrowers, is so incorrect as to be outright misleading. No depositor has ever had their bank balance reduce because the bank lent out what they had deposited.

The simple truth is that banks create new deposits when they issue credit. The amounts that are credited into a customer’s account when they borrow from a bank do not come from government, or from depositors’ bank accounts. They are created at the point of lending, and this is how the money supply grows.

For the accountants among us, the accounting entry is quite simple:

Dr Loan asset

Cr Customer account

That, quite literally, is it.

In legal terms, “[the bank] purchases the loan contract (legally considered a promissory note issued by the borrower) which is reflected by an increase in the bank’s assets by the amount of the loan,”[4] and by a concomitant increase in the bank’s liabilities by the value of the amount credited to the customer’s account.

Further, given that there is virtually no other money creation mechanism in the economy, it follows that 93% of the money in the Kenyan economy (M2) – KES 3.3 trillion as at December 2022 – has been created in this way. This compares with 97% of the money in the UK economy (Ryan-Collins et al, p 6).[5]

Thus, when banks lend, they create new money. In case the reader’s mind finds itself recoiling from this truth, he/she may consider themselves to be in exalted company, for no less a luminary than John Kenneth Galbraith once stated:

“The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled. When something so important is involved, a deeper mystery seems only decent.”[6]

What this means is that practically all the money that appears in the economy enters the economy as credit. Whether this is just or not, the reader may decide for themselves; a brief discussion on this will be contained in the next piece, in which we consider the policy implications of banks’ money-creation power.

But if banks create money…

…how do they fail?

Banks are businesses and all businesses can fail. The technical term for business failure is insolvency. A business’s assets (generally, what it owns) should always exceed that business’s liabilities (generally, what it owes). A business whose assets exceed its liabilities is solvent. A business becomes insolvent when its liabilities exceed its assets. The implication is that even if the business were to sell off all its assets, the funds generated would be insufficient to settle all its liabilities.

Since the excess of a business’s assets over its liabilities is its capital (what the owners’ stake in the business is), when a business’s liabilities exceed its assets, the business has negative capital. In other words, the business needs its owners to inject more capital / equity into the business, a process called recapitalisation. Failure / an inability to recapitalise the business results in that business’s closure.

Applying this to banks, we may infer that the main assets a bank owns are its loan contracts (what borrowers owe it), its own cash deposits with other institutions, and other financial investments. A bank’s main liabilities are its customers’ deposits (since it owes their customers that money). It follows, therefore, that what a bank is owed in loans should always exceed what the bank owes to customers in the form of their deposits. When customers’ deposits exceed loans in value, the bank becomes insolvent, since even if all its loans were paid back, it would be unable to settle its customers’ deposits.

The true value and viability of the loans a bank is carrying on its books, therefore, is critical. If a large enough number of borrowers default on their loans (as happened during the sub-prime mortgage crisis, for example) then the value of the loans the bank is carrying on its books falls significantly, and the bank becomes insolvent. Recapitalisation becomes necessary to prevent bank closure.

(Note: There is another risk – liquidity risk – that arises from depositors wanting all their money sooner than loan repayment occurs. This timing issue can represent a crisis for a bank as well – a bank can be solvent yet illiquid. This is brought on by slowdowns in loan repayment. Commercial banks in Kenya drew on KES 32.7 billion from the CBK’s discount window in January and February 2024, up from zero in January and February 2023. Their need for this funding points to increased liquidity risk in the Kenyan banking sector.)

…why don’t they bail themselves out of financial trouble?

The question then becomes: even if a significant number of borrowers default on their loans, since banks can create money, why don’t they just create enough of it to make the defaults good? Since, as we have seen, banks create money only when they lend, it is not that simple. Secondly, such lending (i.e. banks lending to themselves) is generally illegal. Nevertheless, it has been done.

In September 2008, at the height of the global financial crisis, Qatari businessman Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani was reported to have invested 25.6 billion Icelandic krona (GBP 155M) for a 5.01% stake in Kaupthing Bank. “We have followed Kaupthing closely for some time and consider this to be a good investment,” Sheikh Mohamed said at the time. Kaupthing collapsed weeks later, and still later it was later revealed that “Kaupthing had lent Sheikh Mohamed the cash to buy the stake.” Iceland, whose handling of the financial crisis should be required reading for all policymakers, prosecuted and convicted 4 Kaupthing executives – including the chief executive and the board chairman – and sent them to prison.

(Note: There have been questions about the manner of Barclays’ capital raising from similar sources in 2008. The Serious Fraud Office pursued the matter in court, and charges against Barclays were dismissed and its executives were acquitted.)

The point the author wishes to make, is that self-bailouts are possible, though such activity is illegal. This helps to demonstrate that banks can create money, including for use for themselves. More conventional bailouts will be discussed in the policy implications piece that follows this one.

Conclusion

In this article, we have established that a nation with its own currency creates its own money supply. Perhaps counterintuitively, this money supply is not created by the government, but by that nation’s banks. Despite the seemingly improbable nature of the fact, it is, nevertheless, true. In this fact can be found a partial explanation for how – in an economy with an unemployment rate of 36%, a falling currency, high inflation, high fuel costs, and other severe macroeconomic headwinds – Kenyan banks can post KES 177.8 billion profits in 9 months (to September 2023). These profits – and the drag they create on the Kenyan economy by making bank credit too costly – are traceable at least in part to the inconsistencies in our collective thinking as regards banking and interest rate policy.

In the next piece we shall examine the policy implications arising from the manner in which new money is created.

Footnotes:

[1] This definition has been modified slightly to align with the CBK’s data as per the Depository Corporation Survey, which includes amounts held in money market funds as part of M2.

[2] This definition has been modified slightly to align with the CBK’s data as per the Depository Corporation Survey, which adds foreign currency deposits to M2 to arrive at M3.

[3] As noted in in Note 1, per this data we take M2 as the total money supply, in order to exclude foreign currency deposits, which is the sole difference between M2 and M3 per the CBK data here used.

[4] Werner, Richard A., 2014. “How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same? An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking,” International Review of Financial Analysis, Elsevier, vol. 36(C), pages 71-77.

[5] Ryan-Collins, J., Greenham, T., Werner, R. and A. Jackson (2011) Where Does Money Come From? A Guide to the UK Monetary System (London: New Economics Foundation), page 6.

[6] Galbraith, J. K. (2017). Money: Whence It Came, Where It Went. Princeton University Press.

One Comment