Introduction

In his first article this year, this author highlighted unemployment as being the single most important economic issue facing Kenya today. He cited two solutions to this problem: small-scale, labour-intensive agriculture as the first and primary solution, and tourism. The author then went on to demonstrate that small-scale, labour-intensive agriculture was the first step along the path the Asian Tigers took towards developing, and parsed the policy implications of following that path. In this article, the author explores tourism as a second solution to the unemployment problem.

A brief history of tourism in Kenya

Tourism has long been an important sector of the Kenyan economy. Improved commercial air travel in the late 1950s, occasioned in part by the introduction of aircraft such as the Boeing 707, shrank the globe and led to increased international travel.[1] The development of tourism in Kenya has typically been government-led. The colonial government passed the National Parks Ordinance in 1945,[2] and went on to establish the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife in 1958[3] (in the midst of the Emergency) based on an understanding of tourism’s potential in Kenya.

So it was that in 1963, tourism arrivals stood at 110,200, earning our fledgling nation USD 25.2M (or USD 229 per tourist).[4] Although the post-independence government established the Kenya Tourism Development Corporation in 1965 to investigate, formulate and execute projects for developing Kenya’s tourism industry, there were also serious challenges and threats to the growth of the industry, including rampant poaching, which saw around 100,000 elephants killed between 1973 and 1977. Nevertheless, between 1963 and 1988 tourism receipts grew at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.2%, amounting to USD 404.7M by 1988.[5] In 1987 tourism earnings exceeded coffee earnings for the first time, becoming Kenya’s highest single foreign exchange earner,[6] although this was also occasioned by a fall in coffee export earnings from USD 478.8M in 1986 to USD 236.5M in 1987. (The reasons for this drop in coffee earnings are perhaps worthy of exploration themselves, but we shall stay on topic.) Tourism earnings have generally remained above coffee earnings ever since.

By 2019, the last pre-Covid year, tourist arrivals stood at 2.05 million and total tourism receipts stood at USD 1.6 billion. This activity directly and indirectly supported 1.6 million jobs.[7] Had we maintained a CAGR in tourism receipts of 11.2%, in 2019 Kenya would have earned USD 11B from tourism; had we maintained the CAGR in number of international tourist arrivals of 7.2%, Kenya would have hosted 5.89 million tourists in 2019. (This suggests a per tourist spend of USD 1,880 which is quite high; more on this later.) Tourist arrivals had rebounded from 870,500 in 2020 to 1,321,887 during the first 11 months of 2022, so we shall continue to use 2019 as the benchmark year in this article.

Tourism’s potential

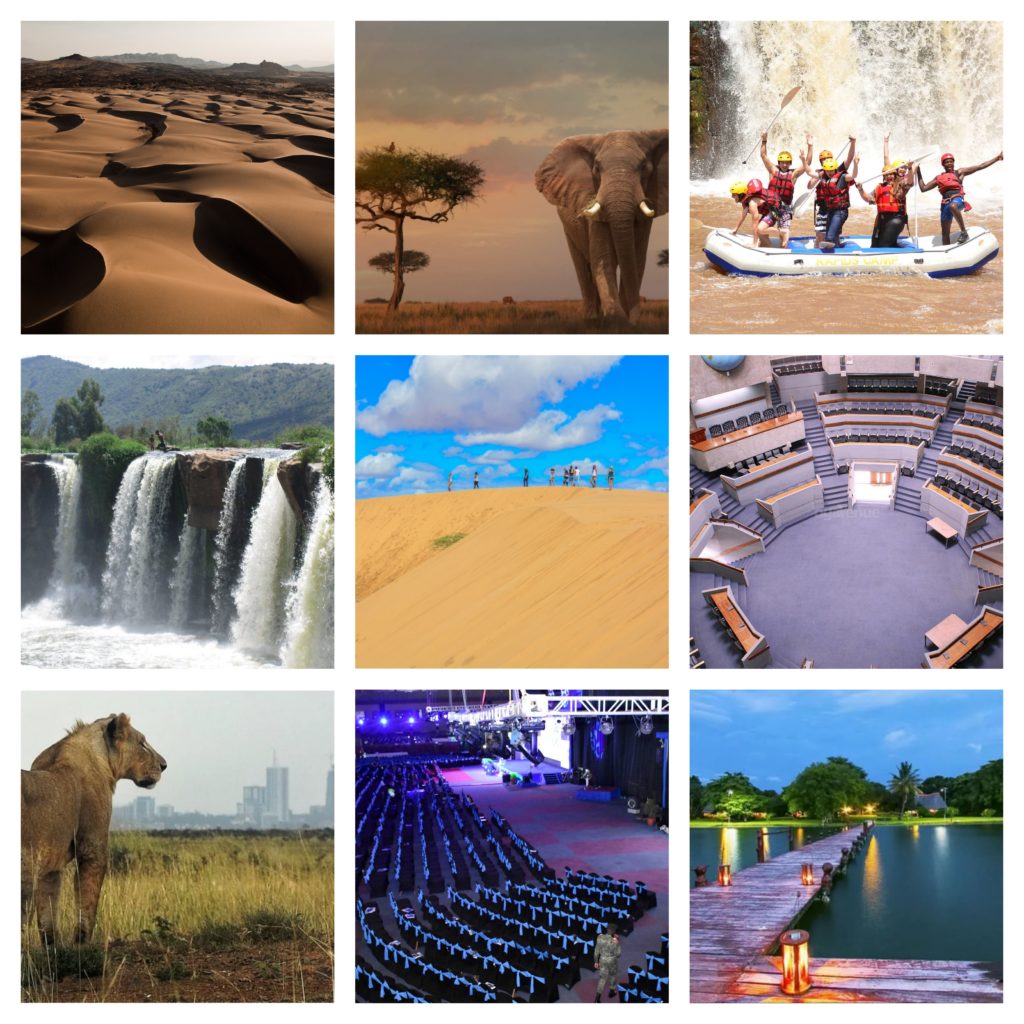

Kenya is deeply blessed with numerous, varied natural and cultural attractions that together provide a unique value offering. The country is endowed with mountains, rivers, waterfalls, lakes, oceans, beaches, deserts, wildlife, palaeontological sites; it also has a rich cultural heritage. Kenya also has suitable conferencing facilities. Together, these advantages should comprise a most compelling package for the international tourist.

Tourism is a labour-intensive sector, which is the reason this author sees it as an important part of the solution to our crippling unemployment. Further – since our unemployed are in a pyramid, with unskilled and semi-skilled workers comprising the bulk of our unemployed – it is important that the solutions we suggest for solving this problem are capable of absorbing literally millions of unskilled and semi-skilled workers into the workforce. Since tourism creates opportunities for drivers, laundrymen and laundrywomen, cleaners, waiters and waitresses, chefs, electricians, plumbers, and farmers, tourism meets this requirement.

Countries which are highly dependent on international tourism have been found to grow faster than their non-tourism counterparts.[8] Figures from a 1969 study in Mexico showed that for USD 80,000 invested in tourism, 41 jobs were created. The same investment was only capable of creating 16 jobs in petroleum, 15 jobs in metal products, or 8 jobs in electricity.[9] Indeed, it was found that a 10 percent increase in local hotel revenues in Mexico led to a 2.5 percent increase in municipality total employment.[10]

(Figures like these are precisely why, in the humble opinion of this author, manufacturing constitutes a far smaller proportion of the solution to our unemployment than is commonly thought. From the point of view of jobs-per-dollar-of-investment – a metric governments and well-meaning non-profits would both do well to adopt – manufacturing does not stack up to tourism (or to agriculture for that matter).)

Mexico, however, is right next-door to America, and so it is worth shifting our comparisons closer home. In 2019, Egypt received 13.1 million tourists, earning it revenues of USD 13.03 billion. Further, domestic and international visitor spending directly contributed USD 20.9 billion to Egypt’s GDP, and an additional USD 8.6 billion in indirect and induced impact; this economic activity contributed 2.5 million jobs.[11] The country’s Ministry for Tourism and Antiquities has a targets to host 30-40 million tourists per year. Morocco, home to the Atlas mountains, beaches on the Atlantic, a rich cultural heritage, and the Sahara, also welcomed 13.1 million tourists in 2019, generating USD 8.2 billion in receipts.

We might say that these two countries’ proximity to Europe hand them an undue advantage, until we learn that South Africa welcomed 10.2 million international tourists in 2019, generating USD 5.7 billion in receipts. (More to our point, tourism employed 773,533 South Africans that year – a third of whom were involved in road transport.) Finally, Uganda our neighbour to the west (with no shoreline to speak of), received 1.5 million tourists in 2019, generating USD 1.6 billion in foreign revenue, while Tanzania, our neighbour to the south, received 1.45 million tourists that same year, generating an eye-watering USD 2.6 billion in revenue. These figures show that compared both to continental peers and to regional peers, we should be doing much better. How can we do so?

Growing Kenya’s tourism

Marketing

Figure 1: The Five Stages of Travel Planning[12]

The Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife states that Kenya has a carrying capacity of 7 – 7.5 million tourists,[13] which suggests that we are operating at less than 30% of our potential.

(How microcosmic this is of our land and nation! There exists a yawning chasm between what we are and what we could be, and we need to be electrified and energized by this.)

Efforts should be made to attain this figure, through targeted and differentiated marketing campaigns that address the specific needs of different markets. Although this is well understood, it appears that traditional marketing approaches are still being used, such as roadshows, trade visits, and/or “familiarisation trips”. The discerning Kenyan reader might well guess the reasons why such outmoded marketing methods are still in use. What would be more effective would be to approach the right trade agents and co-develop a marketing strategy that might, for example, focus on the 10-15 companies who bring the most business to Kenya.[14] A focus on nations such as the Middle East, China, the United States and the United Kingdom, focusing on what the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife has called “the sophisticated traveller, wealthy parents with children, and elite young professionals”[15] would also help.

We live in the age of social media, so another approach might be to leverage the many celebrities who have visited Kenya – being careful to make use of such leverage only apolitically. We may have forgotten it, for example, but Prince William proposed to Princess Kate in these lands, stating that “I could think of no more fitting place than Kenya to get down on one knee.”[16] Serena Williams (2008 and 2010), Jose Mourinho (2010, for 3 weeks), Mark Zuckerberg (2016), Jack Ma (2017), Lewis Hamilton (2022), and Chris Hemsworth (2023) are just a few of the celebrities who have visited our climes. Kenya is all that and more, and people need to know it.

Table 1: 2019 tourist arrivals, revenues and per-tourist spend for selected countries

In addition to increasing our numbers, our marketing approach could also be tailored to ensure that spend-per-tourist is raised, although it is not low, as the table below shows:

It has been shown, for example, that “conference tourism generates much higher rates of expenditure than vacation tourism, a three-fold ratio per diem being quite common.”[17] Few cities in the world can offer the conference tourism package that Nairobi can offer, with its backyard national park. This unique offering, coupled with the fact that Nairobi is home to the African headquarters of the United Nations in Africa, among other regional headquarters, should also be utilised to the full.

Digital approach

We have touched briefly on the social media marketing phenomenon / opportunity above; indeed the brand ambassador has become the social media influencer. Working with celebrities to help them monetize their reach and help Kenya market itself as a tourist destination is not only win-win and sensible, but it would also have a far higher return on marketing investment. Further digital marketing approaches involving the use of commonly used sites like TripAdvisor, and Booking.com etc would be important.

The increased use of digital approaches must not be limited to marketing. Kenya’s e-visa site, for example, should be improved for speed, usability, functionality, uptime and linkages to holiday experiences.[18] Park entry (including the payment of park entry fees) should also be digitized. Thought should be given to making a digital tourist app[19] that could, for example, provide interesting informational pop-ups based on a tourist’s geolocation (“You are now descending the eastern escarpment of the Great Rift Valley. The Great Rift Valley is one of the world’s largest geographical features: it starts in Lebanon, runs through Israel and goes all the way to Mozambique.”) The data such an app would provide would be very rich, and in these times data drives profitability.[20] Further, the on-selling opportunities such digital interaction (lunch?) – provided these notifications would not be too intrusive – would be immense.

The tourist’s experience

The end-result of a successful marketing endeavour is that a promise is made to the potential customer; that promise needs to be kept. Sweeping landscape footage taken from soaring drones can only go so far; if the lived experience of a tourist visiting the country is at variance with the marketed experience, we shall only hurt ourselves.

What, then, is the experience of the tourist once they land at any one of our international airports? Have the staff carrying out health checks, and have immigration staff, who are the tourist’s first points of contact in the country, been trained in professional courtesy? Do these staff speak the languages of the nations whose tourists we have targeted in the marketing phase? What is the Immigration experience like? Have we carried out studies that estimate the optimal number of staff required to manage peak traffic, and hired accordingly? Is Karibu Kenya merely an advertising hoarding, or do visitors to our country actually feel welcome?

This author finds that landing in Kigali is a much nicer experience than landing in Nairobi. At Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, for example, the screen that shows the new arrival where to find their baggage will inform the unsuspecting tourist that his/her flight’s baggage is to be found on Belt A. After a long and fruitless wait at that belt, by which time our visitor may well have begun to resign themselves to the fact that their baggage did not make it, the startled newcomer espies a passenger he/she travelled with walking out with a large suitcase in tow. After a determined investigation conducted through narrowed eye, our visitor discovers that his/her baggage has been surreptitiously scooting about on Belt C. What a welcome for the unwary sightseer! What an initiation into the ways of Kenya! And all this happens before they even leave the airport… We can and must do better.

Infrastructure

Previous discussions about the Asian Tigers’ agricultural take-offs could not include Singapore, which is too small for agriculture to have been viable. As far as tourism is concerned, however, we have much to learn from that island nation. One of the reasons why Singapore, a country only slightly larger than Nairobi county, is able to welcome over 4.8 million tourists a year is because of the development of a level of infrastructure and service delivery that makes processing this number of tourists possible. This did not happen by accident; at one stage Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew required weekly reports on the cleanliness of the toilets at Changi Airport. Kenya must make the infrastructural investments necessary to make our nation an international tourist hub. The Dongo Kundu bypass, which is set to reduce travel times to South Coast by at least one hour, is one such example. Attempts to market Nairobi as a conference destination will soon come up against the wall that the capital is too often gridlocked with traffic. Interventions such as the Lang’ata Road – Mbagathi Way overpass and/or the Bomas interchange should be implemented at all major intersections in the city. Recent plans to lock private vehicles out of the Nairobi city centre are also welcome, provided viable alternatives are available. A safe, secure and effective bus rapid transit system would help greatly in this regard.

Using price to manage tourism

Photos of serried ranks of Landcruisers during the wildebeest migration are a cause for concern. There is scope to limit the number of tourists by charging premium prices so as not to strain our parks’ carrying capacity, thereby protecting our parks. Recent news of a lion undergoing a vasectomy also raises questions. Should we not consider allowing our lions to breed, and then selling trophy hunting (1 lion a year) at a cost of 10 million dollars a head to Middle Eastern princes and sheiks? (Kenya has slightly over 2,500 lions.)

Land use

This author has harped on land use in Kenya on more than one occasion, but will make only a couple of points here: it is not in order for coastal hotels to privatise beachfront land. While they do this for the sake of their guests, it is not feasible to have the land private to these beach hotels. Photos of other coastlines show coasts that are open to the public. Naturally, achieving this would take some doing (see arguments below about GDP per capita), but in such areas of the coast as are yet to be developed, we should not lock out Kenyans from enjoying their own beachfront.

Secondly, vast and/or valuable tracts of viable land that remain unused and that could be put to better use should be taxed. This author has spoken about this in a number of articles (most comprehensively here). The Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife actually suggests that in order to maximise land use we should either impose a land tax on “white land” (open land that has not been developed) or institute build-or-sell policies.[21] This author certainly agrees with these solutions to the problem.

Domestic tourism

Earlier on, we saw that domestic tourism in Egypt was responsible for about USD 8 billion of the receipts from tourism in that country in 2019.[22] Indeed, that year the total number of domestic tourists in the country that year amounted to 19.9 million; 80% of total travel and tourism spending in Cairo was from domestic visitors.[23] In South Africa in that year, domestic tourism generated USD 3.1 billion as 13.5 million South Africans took domestic trips that year.

Domestic tourism is an important method of smoothing the seasonality of tourism. Severe peaks and troughs in tourist arrivals results in non-constant employment, as businesses will resort to hiring casuals to manage peak traffic. This is undesirable not just from an employment or full-time equivalent (FTE) perspective, but also from the perspective that businesses are less likely to invest in non-permanent staff, so that less well trained staff are hired to take care of visitors at precisely the moment when the most experienced and well-trained staff are needed. Domestic tourism helps to even out these highs and lows.

Growing domestic tourism is a marketing issue, but it is also an economic growth issue. Unless the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita grows, it is going to be difficult for domestic tourism to take off properly, since discretionary income is a key driver of this market. Egypt’s GDP per capita in 2019 was USD 2,869; South Africa’s was USD 6,688. Kenya’s was USD 1,970. So that once again we come to the conclusion that our problems are interconnected; unless we work hard at doing everything necessary to make our economy grow, we shall continue to operate at less than 30% of our potential.

Conclusion

It is this author’s contention that tourism has immense potential to reduce unemployment in our country. Kenya possesses – in abundance – the natural and cultural resources to achieve this goal. With these resources, and Kenyans’ hardworking, entrepreneurial and well-educated labour force, there is no reason why tourism in Kenya should not grow to its full potential.

[1] Ondicho, T. G. (2000). International Tourism in Kenya: Development, Problems and Challenges. East African Social Science Research Review. 16(2), 49-70.

[2] Ondicho, T. G. (2000). International Tourism in Kenya: Development, Problems and Challenges. East African Social Science Research Review. 16(2), 49-70.

[3] Ondicho, T. G. (2000). International Tourism in Kenya: Development, Problems and Challenges. East African Social Science Research Review. 16(2), 49-70.

[4] Dieke, Peter. (1992). Tourism development policies in Kenya. Annals of Tourism Research. 19. 558-561. 10.1016/0160-7383(92)90137-E.

[5] Dieke, Peter. (1992). Tourism development policies in Kenya. Annals of Tourism Research. 19. 558-561. 10.1016/0160-7383(92)90137-E.

[6] Dieke, Peter. (1992). Tourism development policies in Kenya. Annals of Tourism Research. 19. 558-561. 10.1016/0160-7383(92)90137-E.

[7] Tourism Economics (2021) Driving the Tourism Recovery in Kenya published by Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics Company.

[8] Pigliaru, Francesco & Brau, Rinaldo & Lanza, Alessandro. (2007). How Fast are Small Tourist Countries Growing? The 1980-2003 Evidence. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.951221.

[9] Ruiz AG, “Effectos del Turismo en La Economía Nacional,” Reunion Nacional de Chápala, Diciembre 2, 1969. Me’xico, D.F., Departamento de Turis

[10] Faber, B., & Gaubert, C. (2019). Tourism and Economic Development: Evidence from Mexico’s Coastline. The American Economic Review, 109(6), 2245–2293. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26737887

[11] Tourism Economics (2021) Driving the Tourism Recovery in Egypt published by Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics Company.

[12] Tourism Economics (2021) Driving the Tourism Recovery in Egypt published by Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics Company.

[13] Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife (2022) New Tourism Strategy for Kenya 2021-2025

[14] Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife (2022) New Tourism Strategy for Kenya 2021-2025

[15] Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife (2022) New Tourism Strategy for Kenya 2021-2025

[16] Sensitivities about conservancies are in order.

[17] Williams, A. M., & Shaw, G. (1988). Tourism: Candyfloss Industry or Job Generator? The Town Planning Review, 59(1), 81–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111677

[18] Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife (2022) New Tourism Strategy for Kenya 2021-2025

[19] Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife (2022) New Tourism Strategy for Kenya 2021-2025

[20] Tourism Economics (2021) Driving the Tourism Recovery in Kenya published by Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics Company.

[21] Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife (2022) New Tourism Strategy for Kenya 2021-2025

[22] From a synthesis of this article and from the article [Tourism Economics (2021) Driving the Tourism Recovery in Egypt published by Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics Company.]

[23] Tourism Economics (2021) Driving the Tourism Recovery in Egypt published by Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics Company.

Thanks Samuel for this article. Captures well the need to seriously consider tourism as a great source of employment and concomitant economic benefits. In my view, experience of the visitor is very to marketing. Our entry points especially JKIA should be staffed by people passionate enough to create a wowing experience for the visitor. Many a time what we have in my view are staff members doing bare minimum as far as quickly helping people coming into the country have a smooth entry. “No hurry in Africa” is practiced many a time. Rude communication and ignorance sometimes with a begging disposition looking for “kitu kidogo” exacerbates the problem. We can do better.